Limehouse, in Stepney, was London's first Chinatown. A small Chinese community in the East End grew in size and spread eastward, from the original settlement in Limehouse Causeway, into Pennyfields. The earliest Chinese migrants to Britain were employed by the British East India Company. They arrived in the East London docklands in the 1780s, aboard merchant vessels carrying tea, ceramics, and silk.

These ships docked in Limehouse, a thriving, industrious entry port and already the most cosmopolitan district, in the most cosmopolitan city, in London. Among the few first-person accounts that exist from Chinese sailors of the period is an oral one given by Xie Qinggao, from the 1780s or 1790s. He reports being impressed by London’s wealth, its imposing buildings, and, perhaps not surprisingly for a sailor, the ready availability of prostitutes.

From roughly 1860 to 1945, the Limehouse district of East London was home to a small community of resident and alien Chinese. Centered on Limehouse Causeway, near the West India Docks, Limehouse had been inhabited since the 16th century by successive groups of ethnic immigrants as well as working-class Anglos. Chinese seamen had sojourned there sporadically since the mid-18th century, but it wasn't until after 1900 that Chinese men, women, and children began to form a visible community.

|

| Pennyfields, King Street, and West India Dock Road area. Plan based on the Ordnance Survey of 1895. |

Limehouse Causeway, Pennyfields, Ming Street, Commercial Road, and West India Dock Road

Until the construction of Commercial Road in 1802, access to Poplar and Blackwall from Limehouse and Whitechapel was through the narrow streets of Limehouse itself, and from there along Limehouse Causeway and Pennyfields into High Street. Following the completion of the Commercial Road, which abutted the western ends of Pennyfields and Ming Street, later renamed King Street, the approach to Poplar's High Street from the west was much improved. That section of the Commercial Road from its junction with the East India Dock Road to the West India Docks was not referred to as the West India Dock Road until 1828, and the name was not widely used until the later 1830s.

It is more for social and cultural history than architectural history that Pennyfields merits recording. Sited at the western end of Poplar's High Street, Pennyfields, with its low-class housing and shops, formed a "buffer" between the shabby respectability of High Street and the exotic Oriental underworld of Limehouse Causeway to the west. During the closing decades of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth, Pennyfields was a strange mixture of both societies. By 1914, this street had become the center of Chinatown's East End. All the buildings associated with the street's colorful past were demolished, however, replaced by public housing during the 1960s.

The Asian Quarter

From the 1880s the Chinese community in London's East End grew in size and spread eastwards, from the original settlement in Limehouse Causeway, into Pennyfields. This, small and relatively law-abiding, Chinese community expanded into two separate communities. Chinese from Shanghai mostly settled around Pennyfields and Ming Street, whereas the immigrants from Canton and Southern China lived generally around Gill Street and the Limehouse Causeway.

The area provided for the Lascar, Chinese, and Japanese sailors working the Oriental routes into the Port of London. The main attractions for these men were the opium dens, hidden behind shops in Limehouse and Poplar, and also the availability of prostitutes, Chinese grocers, restaurants, and seamen's lodging houses. Hostility from British sailors and the inability of many Chinese to speak English fostered a distinct ethnic segregation and concentrated more Chinese into Pennyfields.

Gradually the drab shops of Pennyfields were transformed into Chinese emporia and their colorful interiors became an exotic contrast to the grey streets of Poplar. "The Chinese shops are the quaintest places imaginable. Their walls decorated with red and orange papers, covered with Chinese writing indicating the "chop" or style of the firm, or some such announcement. There is also sure to be a map of China and a hanging Chinese Almanac."

The heady scent of burning opium, joss-sticks, and tobacco smoked through the air, producing an atmosphere much sought after by the literary and artistic coterie of fin-de-siècle London. Pennyfields became a "sight" for West End society. From the 1890s until the 1930s, parties regularly went east at night, expecting to find the unusual and morally degenerate in Pennyfields. Instead, they found a commonplace street. The Pennyfields of legend was always more exciting than that of reality. But it was different from the rest of Poplar: "In the darkness of Pennyfields dark-faced men are passing. Over the restaurants and shops are Chinese names."

Forgotten History

Apart from census data and one sociological study conducted in 1962, when many of the early immigrants were still alive, little is known about the Chinese of Limehouse. The community appeared and then vanished quickly in the brief space between two world wars.

It's known that in the 1910s and 1920s, most of the immigrants were young men employed as seamen or dockworkers. The rest were laundrymen, shopkeepers, or restaurateurs. Very few of them operated or worked in gambling houses and opium dens.

Once they had established themselves, the men would send for their wives and other family members. However, it was not uncommon for Chinese men to marry working-class English women. It's known that for recreation these immigrants partook of small-scale gambling and, less commonly, opium smoking. They also gathered socially to share the news and newspapers they received from home as there was no Chinese newspaper published in London during this period. There were trade clubs, too, as well as a Chinese Masonic Hall, whose members supported the 1911 revolution in China to overthrow the Manchus and end the Qing dynasty.

About the immigrants' children, little is known. A philanthropic society set up a Chinese school for them in 1935, and its one teacher taught in Cantonese. Just before 1939, however, the teacher was accused of communist activities and deported. The school closed and never reopened.

Since the Chinese of Limehouse were a small and orderly community, who rarely competed with Anglos for jobs, they remained invisible to a certain extent. Thus, it seems, they escaped much of the systematic violence with which Anglo-Londoners greeted other immigrant groups, such as Germans and Russian Jews.

The only recorded instance of sustained or organized hostility was that of British seamen opposed to the British merchant marine's employment of the Chinese, who worked for low wages and sometimes served as strikebreakers. This hostility came to a head during the 1911 seamen's strike when strikers destroyed about thirty Chinese homes and laundries in Cardiff. However, this seems to have been an isolated incident. There was no such violence, none reported at least, against the Chinese of Limehouse.

In fact, before World War I, the community was still too tiny to attract much notice at all. In his chapter on "The Alien" in East London, Walter Besant states dismissively that "Compared with the Chinese colony of New York... that of London is a small thing and of no importance". In a study of pre-war attitudes toward the Chinese in London, Liverpool, and Cardiff, one researcher has concluded that "although occasional notes of disquiet were expressed with respect to the Chinese presence" at this time, other evidence points to "attitudes of indifference and even acceptance".

Records show, the public occasionally raised objections concerning the two "Chinese vices" of gambling and opium smoking. However, the police considered these activities harmless and generally looked the other way. As for the Chinese-Anglo marriages, there is not, thus far, any evidence of public concern.

Police did investigate one matter in Limehouse when a British school headmistress accused two Chinese men of corrupting teenage girls. But an inspector in charge of the case concluded "the Chinaman if he becomes intimate with an English girl does not lead her to prostitution but prefers to marry her and treat her well". In A Wanderer in London, E.V. Lucas reports the "silent discreet Chinese who have married English women and settled down in London are, I am told, among the best citizens of the East End and the kindest husbands".

Chinatown is Noticed

Before 1911, the Chinese of Limehouse were either accepted or simply unnoticed by London's other residents. As one researcher states, these Chinese were "of little concern to the majority of Britons amongst whom they lived and worked and created no significant problems for the authorities". However, this situation soon changed.

The population of Chinese in Limehouse was still small compared with those of other immigrant communities in London. In fact, Liverpool had a far larger Chinese population. Yet suddenly, the Chinese community in Limehouse and Poplar districts was "noticed". In the space of a few years, the all-but-invisible Chinese quarter became known as "Chinatown" by 1911.

By 1914, the Chinese community burgeoned with new restaurants and shops.

Late in 1915, with nightlife in London driven underground by wartime regulations, rumors began to surface about cocaine use among young women who frequented clubs. Over the following months, reports about cocaine use by prostitutes raised fears that they might spread the habit to soldiers.

These fears were sharpened by the realization that, as it was not illegal to take cocaine or any other drugs, there was little the law could do about it. Stoked by sensational headlines, "Cocaine Driving Hundreds Mad - Women and Aliens Prey On Soldiers", concern boiled into a panic. In July 1916, the possession of cocaine and opium was criminalized by an order made under the Defence of the Realm emergency powers act. The nascent British drug underground was now outside the law.

By 1918, the number of Chinese living in Pennyfields alone totaled 182. All were men. Nine of them had English wives.

Chinatown is Demonized

Circa 1918, despite the peaceful and law-abiding nature of Chinese people living around Limehouse, this Chinatown developed an extraordinarily bad reputation. During this period, Chinatown was less dangerous than any other area of the East End. Still, it was demonized amid fears of criminality and deviancy in Limehouse.

Newspapers and magazines wrote scandalous articles with lurid headlines about opium dens and the white-slave traders. Numerous writers, novelists, and even filmmakers helped to greatly exaggerate the danger and immorality of the area. At times, it seemed that Limehouse was almost singlehandedly responsible for corroding the moral backbone of the British middle-classes.

This change in public perception of Chinatown was wrought primarily by two popular fiction writers whose works suddenly gave Limehouse, as Chinatown, a negatively discursive presence it hadn't possessed before. Sax Rohmer and Thomas Burke set many of their stories in Limehouse. In fact, this district became an obsession for both writers.

For both these authors, Limehouse was London's true Orient. It was a local urban territory. It was an integral part of their city's "dark underworld" of native and immigrant slum-dwellers, because of what they saw, or imagined to be, its specifically Chinese character. The fiction they produced about Limehouse helped situate it within an already complex and polysemous imaginative cityscape.

Rohmer's first Fu Manchu story was published in 1912. Rohmer's first Fu Manchu novel was published in 1913. Rohmer's The Yellow Claw was published in 1915. Romer's Tales of Chinatown was published in 1916. Rohmer's second Fu Manchu novel was published in 1916. Burke's Limehouse Nights was published in 1916. Rohmer's third Fu Manchu novel was published in 1917.

In 1918, newspapers reported on the death of a young actress, Billie Carleton, and the scandal that followed. The coroner's examination found Carleton had died of a cocaine overdose. An inquest also revealed her connection to an opium operation run by a Scottish woman, Ada Ping You, and her Chinese husband, Lo Ping You. Ada and Lo lived in a dilapidated house on the eastern end of Limehouse Causeway.

In 1919, Sax Rohmer's novel Dope was published. The character Rita Dresden was based on Carleton.

By 1920, many of the houses occupied by the Chinese were described as "very old and in many cases extremely dilapidated externally". Internally most were clean, uncrowded, vermin-free, and less susceptible to infectious diseases than their English neighbors.

In 1922, newspapers reported on the death of a young dance instructress, Freda Eileen Kempton, and the scandal that followed. She died of a cocaine overdose. An investigation into the circumstances surrounding her death revealed a connection to Brilliant Chang, a Chinese restaurateur, charming womanizer, and drug dealer. The British popular press portrayed him as an international drug mastermind and the first celebrity "Dope King" of London.

The fact that Chinese enjoyed gambling and smoking opium was bad enough. However, it seemed to be the fear of sexual contact between Chinese men and "white women", which the drug-taking only exacerbated, that terrified so many Londoners, especially newspaper editors of the time. One headline from the Evening News proclaimed "White Girls Hypnotised by Yellow Men". The article claimed that it was the duty "of every Englishman and Englishwoman to know the truth about the degradation of young white girls".

By the middle of the 1920s, Chang had been deported and the first British drug underground had died down. The distinctive themes of the panic that went with it – young women seeking pleasure, young women making bad choices, young white women associating with "men of colour" – expressed the deepest anxieties of their time. They shaped ideas about drug abuse for decades afterward and their echoes can still be heard today.

In 1925, Sax Rohmer's Yellow Shadows was published which features a Chinese villain by the name of Burma Chang. It's most likely that character was based on Brilliant Chang.

In 1926, H.V. Morton, the famous travel essayist and journalist, wrote about Limehouse in his book The Nights of London:

"The squalor of Limehouse is that strange squalor of the East which seems to conceal vicious splendour. There is an air of something unrevealed in those narrow streets of shuttered houses, each one of which appears to be hugging its own dreadful little secret… you might open a filthy door and find yourself in a palace sweet with joss-sticks, where queer things happen in a mist of smoke... The silence grips you, almost persuading you that behind it is something which you are always on the verge of discovering; some mystery of vice or of beauty, or of terror and cruelty."

In 1930, China-born residents of Limehouse numbered approximately 2,000. These figures do not account for their London-born children or grandchildren. At its maximum size in 1939, Chinatown consisted of 5,000 persons, many of whom were sailors.

Chinatown is Demolished

In 1940, London was systematically bombed by the German Luftwaffe Blitz. At this time, residents abandoned Limehouse and dispersed into other areas of the city. Limehouse sustained extensive damage during the blitz.

A few Chinese returned after the war. They remained in Limehouse and Pennyfields until the early 1960s. In 1963, the city demolished most of the remaining buildings in the Chinatown area and replaced them with public housing. It then suffered a "dead" period until gentrification began in the 1970s.

A Phoenix Rises from the Ashes

London’s Chinatown relocated to Soho, centered on Gerrard Street, in the 1960s. Soho, which was once populated by seedy sex shops and cabarets, has since become one of London's most exclusive, expensive, and popular cultural hotspots. Whether through fortune or foresight, the once-vilified community of Chinatown seems to have the last laugh.

|

| circa 1900 A group of happy children playing in a street in London's Limehouse. |

|

| circa 1900 A youth standing outside C Middleburg's sacks and bags shop in London's Limehouse. |

|

| circa 1900 Children playing in a street in London's Limehouse. |

|

| circa 1910 People walking down Limehouse Causeway in London. |

|

| 1911 A street in Chinatown London, home of the Wo Fung Goy Chinese Cafe. |

|

| 1911 A street in Limehouse, London's Chinatown. |

|

| 1911 A street in London’s Chinatown. |

|

| circa 1924 A Chinese shop in Pennyfields, London. |

|

| 1925 A mother and child looking over the bottom half of their front door in Limehouse, London. |

|

| 1925 Dupont Street, Limehouse. Rooftops are covered to keep out the rain and the houses have no windows. |

|

| 1925 Limehouse Causeway. |

|

| 1925 Men bringing out cured fish ready for dispatch in Limehouse, London. |

|

| circa 1925 A street in the slum area of Pennyfields, Limehouse, London. |

|

| circa 1925 Dunbar House on the West India Dock Road, Limehouse, London. |

|

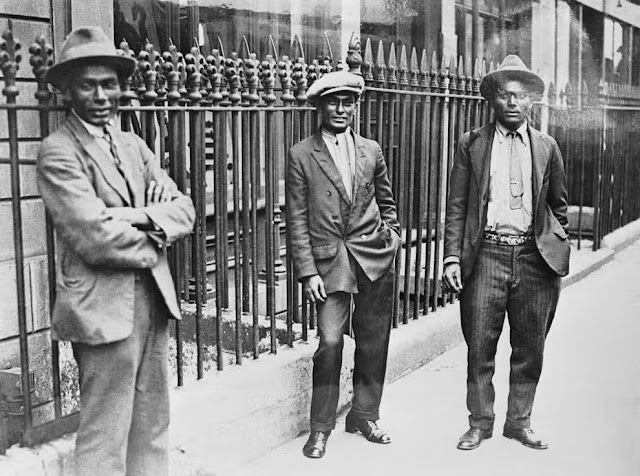

| circa 1925 Three seamen outside Dunbar House on the West India Dock Road, Limehouse, London. |

|

| 1927 Children walk and play outside the Chinese Freemason Society in Limehouse in London's Docklands. |

|

| 1927 The Rev FH Higley of the Church of Our Lady Immaculate climbs to the top of a ladder on the site where he is building a church at Limehouse, with the assistance of his congregation. |

|

| 1928 Anna May Wong in Limehouse Causeway. |

|

| 1929 Politician Evan Morgan, Conservative Party candidate, canvassing for votes in his constituency in the fishing yards of Limehouse, London. |

|

| 1930 Pennyfields and Limehouse Chinese shop on the corner of Turners Buildings in east London. |

|

| circa 1935 London’s Chinese quarter, Chinatown. |

|

| 1936 November Limehouse Causeway |

|

| 1936 A diver at work unloading a sunken barge loaded with 55 tons of Manganite which sank in the Limehouse Cut, a canal connecting the River Lea with the Thames at Poplar. |

|

| Children in Chinatown, the East End of London. |

|

| Pouring tea in Chinatown. |

|

| Two Chinese men meet on a street corner in Chinatown. |

|

| Barges waiting for access to Regents Canal from Regents Canal Dock, viewed from one of two new electric coal dischargers erected at the dock at Limehouse. |

|

| A Fog scene at Limehouse Reach. |

Sources:

https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols43-4/pp111-113#anchorn27

http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/14192/1/14192.pdf

Additional Resources

Sax Rohmer's Limehouse

Limehouse Maps 1888 & 1912

No comments:

Post a Comment